Subcommittee on Antitrust and Monopoly,

Hearings on Government Intervention

in the Market Mechanism: Petroleum,

Part 1, 1969, pp. 578-599.

I don't have a copy of the published document; instead, I worked from a typed draft of the paper. This online copy of the published document, Governmental Intervention in the Market Mechanism: The Petroleum Industry (HathiTrust Digital Library), can be viewed page by page; you must be a member institution in order to download the document in full. In any case, Dr. Measday's article begins on page 578, halfway down the page.

The supply of domestic crude oil is to a large extent regulated by State governments; the principal role of the Federal government is to limit imports to a level which will not disturb the market. A review of the historical background of the cooperation between the Federal government and the oil industry may be helpful in understanding the present attitudes of Federal authorities, particularly within the Department of Interior.

The early history of crude petroleum production was characterized by enormous waste. Under the common law rule of capture, once a field had been brought in there were no incentives (and, indeed, positive penalties) for individual conservation. [1] As late as 1929, the Department of Interior could point to:

"... the recent record of two wells (on Federal leases) in California which have already turned into the pipe lines nearly $5,000,000 worth of oil and gas but from which gas and gasoline vapor worth more than $10,000,000 have gone up into the air—a total loss to present and future citizens of the State." [2]

The initial approach to control of production was couched in terms of physical conservation. If any one individual can be credited here, it would be Henry L. Doherty, the architect of and power behind the Cities Service empire. As a result of his experiences in the mobilization of the industry during World War I, Doherty became convinced that a conservation program was essential. Further, in the face of the united opposition of the rest of the industry, Doherty concluded that the only hope lay in a program of compulsory unitization of fields, to be enforced by the Federal government. [3]

With his emphasis on physical conservation, Doherty was unable to convince his colleagues in the industry of his point of view. Although he himself was a director of the American Petroleum Institute, the API board time and again refused him permission to present his case openly at API meetings. [4] Finally, Doherty took an action which branded him "as an enemy to his class". In late 1924 he wrote directly to President Coolidge, calling upon the President to introduce legislation for compulsory unitization, and assuring the President that a proper conservation program would at least double or triple recovery of oil. Pointing out that the mass of bankers had opposed creation of the Federal Reserve System, Doherty stated:

"I am satisfied that the attitude of the men in the oil business will be no different from the attitude of the bankers except in degree, and that for the worse rather than the better. You need only recommend to a group of oil men that they should themselves seek legislation and the mere suggestion will throw them into a panic." [5]

It is generally agreed that Doherty's letter was one of the important causal factors which underlay President Coolidge's creation of the Federal Oil Conservation Board (composed of the Secretaries of Interior, War, Navy, and Commerce) in December 1924. [6] While the Board accepted Doherty's position on the desirability of unitization and conservation, it did not accept the role for the Federal government proposed by Doherty. Instead, from the very beginning, there emerged a pattern of Federal concern for the interests of the industry which has characterized petroleum policy for four decades. And, from the beginning, the Board showed itself more concerned with "economic waste" (i.e., production in excess of market demand) than with physical waste. At this point it should be made clear that "avoidance of economic waste" in the petroleum industry refers solely to the restriction of supply by a regulatory agency in order to maintain a profitable level of crude prices.

In its first report, the Board denied that the Federal government had or should have the power to regulate development and production, except on its own lands. Instead, reliance should be placed upon the States, and cooperation among the States should be encouraged:

"There should be active cooperation among the States in the study of proposed legislation to the end that uniform laws may be enacted, or even agreements or compacts entered into between the States, subject to ratification by Congress." [7]

The Board recognized that State action might take some time. Therefore, as an interim alternative it recommended voluntary cooperation among producers—which should be declared exempt from the antitrust laws.

"The question of the legality of cooperative agreements has frequently been raised in the recent discussion of remedial measures. The uncertainty as to whether the economic betterment through substituting cooperation for competition runs counter to Federal and State laws has served as an actual or imagined or pretended barrier to cooperative action ... This doubt should be removed by appropriate legislation." [8]

Nor were the members of the Board entirely naive about the economic effects of the "conservation" program they were proposing:

"If the several oil-producing States should protect property rights in oil produced from a common underground supply, it undoubtedly would have some effect in the direction of stabilizing production, of retarding development whenever economic demand does not warrant, and of making the business of oil production more economical. Such legislation, although not directly regulating production, would in part accomplish this by freeing owners and operators from the present pressure of a competitive struggle." [9]

This apparently innocuous first report has been quoted extensively because it has an importance far greater than has been recognized by other writers on petroleum policy. In the first place, its emphasis upon the replacement of competition by cooperation must have done much to allay the fears of the petroleum industry about governmental attitudes. Certainly, within a year or two, the adamant opposition of the industry to any sort of governmental intervention had given way to a view that government could be a useful ally. Second, and perhaps most important, one sentence in the concluding paragraph of the report best expresses the developing approach of public policy towards the petroleum industry through 40 years of prosperity and depression, peace and war, Democratic and Republican administrations:

"The complete organization of cooperative effort is recommended, with simple but effective working units that will insure full contact of the industry with both State and Federal governments and continuous contact between all operators in an oil field." [10]There has never been a better description of the organization of the petroleum industry as it exists today. This is one recommendation of a Federal Board which has been fully implemented.

The second report of the Board (January 1928), while not germane to the subject of this memorandum, is of considerable interest. Focusing upon the availability of substitute products for crude oil, it illustrates the extent of knowledge at the time in this area and at the same time leads one to wonder why, in industry or government, so little has been done to act on this knowledge in the past 40 years. The report discusses four possibilities:

It must be emphasized that this 1928 report was not devoted to "blue sky" speculation about some vague future. Every one of the possibilities discussed was known to be technologically feasible at the time the report was prepared. It may be moot, but it is hardly inappropriate to speculate that if the resources expended in developing "Platformate" and other gasoline additives, automobile fins and chrome, "Tigerama" contests, and the like had been used instead to improve and develop these 40-year-old technologies, the benefits to society would have been incalculable.

The third report of the Board (February 1929) consisted of brief introductory remarks plus some appendices which were a significant expression of attitudes in both the domestic and foreign areas. Two of the appendices dealt with "conservation" on the domestic scene—each defining "conservation" to include the curtailment of output during periods of actual or threatened "overproduction".

The first of these was a report of the "Committee of Nine", appointed by the Oil Conservation Board to advise on Federal legislation. Presumably, the Committee was "balanced", with three members each from the industry, the legal profession, and the Federal Government. In fact, it was heavily stacked; two of the three legal representatives were oil company lawyers and at least one of the Government people was pro-industry. [11] The principal recommendation of this committee was:

"Federal legislation which shall (a) unequivocally declare that agreements for the cooperative development and operation of single pools are not in violation of the Federal antitrust laws, and (b) permit, under suitable safeguards, the making, in times of overproduction, of agreements among oil producers for the curtailment of production." [12]

The Board had also requested the American Bar Association to appoint a committee to consider State action. Needless to say, this committee was also heavily weighted with industry lawyers. The ABA committee recommended compulsory unitization of pools, with a proposed law to accomplish this; so far as limitation of production, they expressed the opinion that this should be done on a compulsory basis, and could be done within the framework of their proposed statute. They refrained from making this a specific recommendation, however, because "we are by no means certain that the industry at present is prepared to go that far." [13]

The ABA committee held precisely the same attitude towards State antitrust legislation as the Committee of Nine held towards Federal law:

"In this view, your committee concludes that if the antitrust laws of the oil-producing States are obstacles to the things which the petroleum industry is seeking to accomplish as aids to conservation, those obstacles should be removed, regardless of technical considerations." [14]

The Third appendix to Report III was a technical study of world crude oil resources. While the comments of the Oil Conservation Board on this report were innocuous in themselves, they gain importance in the light of subsequent developments. Pointing to the fact that the U.S. had produced 68% of the world's crude oil in 1928, with only 18% of world reserves, the Board called for an increase in imports, expansion of American investment abroad, and recognition of the fact that studies of the domestic situation could not be isolated from consideration of international trends, all in the name of "conservation". This appendix, said the Board, was not published to tell the oil companies where foreign oil existed, since they already knew:

"... rather, the intent is to acquaint the general public with the nature of these resources and to create that better understanding of the foreign fields which is essential to a sympathetic support of American oil companies now developing foreign sources of supply." [15]

It is no coincidence that, within a month, the API had adopted a proposal for worldwide cartelization of crude production, following the framework of the 1928 Achanarry Agreement (negotiated among Jersey Standard, Royal Dutch-Shell, and Anglo-Persian Oil). [16] Under the proposal, "The entire world was to be divided into zones, among which interzonal agreement would be drawn up limiting output in each zone." [17]

This proposal was presented to the Oil Conservation Board (i.e., the Secretaries of Interior, Commerce, War, and Navy) for approval, with full confidence that such a course of action had a "green light" in view of the Board's sentiments in Report III and the presence of Board representatives at the API meeting which developed the proposal. The board, however, was warned by the Attorney General that it possessed no authority to grant antitrust immunity to anyone. This action did little to change the course of history, since the major U.S. producers entered the international cartel anyway; nevertheless, it is an interesting commentary that, except for the opposition of the Attorney General, U.S. participation in the cartel might well have taken place with the official blessing of the Federal Government.

The suggestion above that at least four Cabinet officers, members of the Oil Conservation Board, favored official cartel participation is not mere speculation. Report IV (1930) need be mentioned only in passing as laying some foundation for the next report; in Report IV, the concept of "conservation" is extended from crude production to the refining operation, since true "conservation" requires a balanced approach to all functions rather than concentration on a single area of the industry. [18] In the same period, a combination of depression and discovery of the East Texas Field had driven crude prices to as low as 10¢ a barrel.

Thus, in Report V (1932), the Oil Conservation Board called for the immediate formation of an interstate oil compact organization which would—in the name of conservation—control both the production of crude oil and refinery output. Further, the Board suggested that in the international area such a group of State could accomplish what was prohibited by the antitrust laws to private companies. Among the functions to be carried out by the proposed interstate oil compact agency was the following:

"Cooperation with Federal agencies in negotiating agreements with foreign producers or producing nations. Oil once produced will find a market. If international markets are to be fairly allocated, and our foreign markets protected, the allocation requires reciprocal agreements on international production quotas. Under our constitutional system the consumation of such agreements is a Federal prerogative, but the enforcement of them is the State's, whose police power is essential to such enforcement. An interstate compact would enable the States, through their interstate body, to assist the Federal representatives in negotiating agreements which the compacting States could enforce as their municipal laws." [19]

During this same period, the Federal Government began to emerge in the role of official "forecaster" of crude oil demand for the industry. To quote Zimmerman (with emphasis added):

"On March 10, 1930, Secretary of the Interior Ray Lyman Wilbur initiated a procedure that has become an integral part of the national program through which the oil conservation problem functions to this day. This was a program of demand forecasts by the government." [20]

From 1930 until the New Deal, the forecasts were provided to the Board on a semiannual basis by "volunteer committees of petroleum economists"; the "volunteers" were provided by the oil companies and the reporting program was initiated at the request of the American Petroleum Institute. [21]

In view of the controversy among academic observers, continuing to the present day, as to the influence of forecasts on production, it is important to note that from the outset of the program, the Board, the API, and the industry expected these forecasts to be the basis upon which production could be regulated. The principal criticism of the early forecasting program, voiced in the Board's Report V, was that the forecasts were "lacking authority" so long as no effective agency existed to enforce them as production controls. This is clearly illustrated by two of the three "requisites" for the industry which could be met by a strong interstate compact (emphasis added):

"1. The initial requisite is an agency which can effectively forecast demand and allocate among producing States production quotas to supply it. Informal forecasts of such a character have heretofore been made by this board's voluntary committees on petroleum economics, at the request of the American Petroleum Institute. As such forecasts are necessarily lacking in authority, and as the Federal Government can give them none which the States need follow, any permanent fact-finding group should be an interstate agency coupled with Federal participation ...

Such an agency could periodically forecast demand in this country and for export, and estimate requirements for domestic crude oil production, drafts on stocks, and imports, in order to meet that demand ... Having made these findings, it could certify to member States and to the United States the respective State production quotas.

"3. Provision should be made for enforcing the production quotas which the fact-finding agency recommends and certifies. Such quotas would be of two classes—domestic production and importation. The following methods may be considered:

(a) As to domestic production: The compact may, if the States desire it, obligate each State to make its quota effective; but each State must necessarily be free to do so by such legal machinery as it sees fit, and solely under its municipal law ...

(b) As to imports: Regulation can be accomplished only by Federal agencies. The compact itself cannot, therefore, be expected to provide for enforcement of any import quota, although it should, as above suggested, provide for cooperation by the interstate body in its determination. Assuming that a scientific forecast has been made of the quantity needed, there are two general methods of restricting imports to that figure—a flexible tariff and proration. The Federal statute which authorizes the compact or ratifies it should, therefore, implement the compact by one method or the other." [22]

While it is difficult to see many significant differences between the approach proposed by the Oil Conservation Board in 1932 and the situation which obtains today, at least one informed writer interprets the proposal as calling for a Federal fact-finding agency whose quota recommendations would be made binding through the interstate compact. Zimmerman remarks: "... it is interesting to observe how close we came to something akin to Federal control of production. How and why this fate was avoided will be discussed later." [23] His deferred explanation (in the pages he cites) appears to be that in the ultimate organization of the Interstate Compact to Converve Oil and Gas, the proposal of Governor Marland (Oklahoma) that the Compact organization have the power to require individual States to follow "the Bureau of Mine estimates" (sic!) was defeated by Governor Allred (Texas) who insisted that no State be legally bound to observe the quotas. Thus, "in this watered-down form" of the Compact, "whatever interstate collaboration there may be is purely voluntary." [24]

Report V was the final report of the Federal Oil Conservation Board. With the coming of the New Deal a few months later, the Board ceased to exist, and its functions were assumed by the Petroleum Code authorities. From this analysis of the background and the work of the Board, it seems evident that it was during the time period occupied by the Federal Oil Conservation Board that the structure of Federal-State-industry cooperation which has characterized petroleum policy ever since was, in fact, developed.

As a prelude to the developments under the New Deal, it should be noted that by mid-1933 the industry was in a state of complete chaos. With the lack of effective interstate cooperation and the controversy over the question of limiting production to market demand, State policies were confused. Much of the confusion arose over the distinction between physical waste and "economic" waste referred to earlier.

So far as physical conservation is concerned, there was little doubt about State powers. As early as 1900, the U.S. Supreme Court had upheld the 1891 Indiana statute prohibiting the flaring-off of gas from oil wells; the right of the State to conserve natural resources over individual property rights in the industry. [25] Thus, many States had physical conservation laws, respecting specific wasteful practices, at an early date—although the enforcement of these statutes was frequently academic, and none related overtly to the control of production.

Economic waste, on the other hand, by its very definition involves the restriction of production for the purpose of maintaining a given level of market prices. In the words of one authority:

"Economic waste is identified with pecuniary losses caused by unduly depressed prices. Hence the adjustment of production to consumption needs is assumed to prevent or reduce economic waste." [26]

It should be observed that the avoidance of physical waste is completely defensible; improper drilling and pumping not only involves present waste, but also sharply reduces the ultimate recovery possible from a field. The avoidance of economic waste, on the other hand, in practice has been nothing more or less than the control of supply for purposes of price fixing. From an early date there appears to have been a division of opinion on this subject between the major companies (who can afford to take a long range view) on the one hand, and on the other the smaller independent crude producers (who wish to get while they can) and nonintegrated refiners (who want low-price crude).

Oklahoma took the lead in the development of State-wide prorationing. Its 1915 statute included economic waste, and the regulation of production to prevent it, as proper goals for State action. [27] With rising World War I prices for crude, it was pretty much forgotten for a number of years. The expansion of Oklahoma crude production in the 1920's, however, renewed fears of surpluses. In 1927, the State produced nearly 280 million barrels, well ahead of both Texas and California. In the following years, therefore, the Corporation Commission issued a state-wide prorationing order (upheld in both the Oklahoma Supreme Court and the U.S. Supreme Court) [28]: between 1928 and 1931, Oklahoma production was reduced by more than one-third, while the State's share of the U.S. total fell from 29% to 19%. [29]

Oklahoma's efforts were negated, however, by the developments in Texas. The State's first statute, enacted in 1919, gave broad powers to the Railroad Commission, which promulgated a number of rules aiming primarily at the curtailment of physical waste. As soon as the Commission showed any sign of going beyond this, the legislature intervened. [30] The statute was amended in 1929 expressly to prohibit the Commission from any consideration of economic waste in its regulations—at the time that Oklahoma was reducing output, on economic grounds, and just prior to the opening of the East Texas field.

Control of the East Texas field, developed by a large number of small operators, proved to be beyond the ability of the Commission. The first regulatory order was generally ignored by the operators, some of whom sued in the Federal District Court to enjoin the Commission from enforcing it. Here the impact of the 1929 amendment became clear—the Court found the order to be simply a price-fixing measure based upon a concept of "economic conservation" which the Commission had bee specifically forbidden to employ. [31] East Texas production rose to a million barrels a day (roughly one-third of the national demand for crude), and prices collapsed. On August 17, 1931, Governor Ross S. Sterling declared martial law, placing the East Texas field under control of the State Guard. Following a hearing, the Railroad Commission set allowables for the field at 400,000 barrels a day, which was the figure enforced by the military authorities. [32] As it turned out, the Railroad Commission was as much upset as the private operators by the military occupation; it washed its hands of East Texas with the complaint that military control had reduced the Commission to figurehead status. The U.S. Supreme Court found the Governor's action to be unconstitutional, since he had interposed his authority to accomplish a result enjoined to the Railroad Commission by the lower Federal Court. [33]

Finally, at another special session in November 1932, the Texas Legislature passed the Market Demand Act of 1932, which with some revision is still the basic law of the State. [34] This act not only annulled the earlier prohibition against consideration of "economic waste", but specifically provided that market demand would be a factor in the establishment of field and well production rates. But at the time even this statute did little to help the Railroad Commission with the problem of East Texas. The Commission proceeded to establish a total field allowable for East Texas of 290,000 barrels a day which was both ignored by the operators and enjoined by the courts. In April 1933, the Commission figuratively threw up its hands and raised the East Texas allowables to 750,000 barrels a day (a quarter of the national demand)—while this was to a considerable extent evaded (by "hot oil" shipments to Louisiana refineries), it was not enjoined!

This, then, was the state of affairs at the time of President Roosevelt's inauguration. The inability of the Texas Railroad Commission to control East Texas production was the principal factor in the collapse of the Oil States Advisory Committee organized in 1931, as the forerunner to the Interstate Oil & Gas Compact Commission, to coordinate State efforts to reduce production. Two other contributory factors may be mentioned, each of which occurred in 1932 [35]: First, the interstate compact drafted by the Committee, to be sponsored by the Federal Oil Conservation Board and designed to establish a national control program, was opposed by the Independent Petroleum Association of America which withdrew from any support of or participation in the work of the Committee. Next, the Texas Railroad Commission was informed by the Attorney General of the State that it was required by statute to fix allowables through its own judgment and could not, therefore, legally enter into any agreement with other States which would bind Texas to accept quotas set by the group as a whole. Clearly, unless Texas (with more than 40% of domestic production at this time) could be brought unequivocally within the ambit of any interstate control program, there was absolutely no reason to even attempt such a program.

Early in 1933, fed by the Railroad Commission's April increase of East Texas allowables to 750,000 barrels a day, the flood of oil increased, and prices once again dropped as low as 10¢ a barrel at the field. [36] The National Industrial Recovery Act, signed by President Roosevelt on June 16, 1933, opened the next phase of petroleum controls. Opposition to Federal intervention had evaporated in the face of the failure of State action or voluntary cooperation to bring relief. Practically en masse, the industry, led by the American Petroleum Institute, marched on Washington to demand federally-enforced cartelization.

An indication of the goal of the Roosevelt Administration towards petroleum policy is provided by a phrase used by the President. In his letter approving the code to General Hugh S. Johnson, Roosevelt begins one sentence with the clause, "In view of the fact that we shall thus soon have a self-governing industry under Federal supervision..." [37] All phases of the industry, in other words, were to be organized into a comprehensive "self-governing" cartel. The only question was whether the "Federal supervision" was to be exercised in the protection of the public interest or as the force by which the cartel could make its decisions binding. Subsequent events show that the Government played the latter role.

Shortly after the National Industrial Recovery Act was passed, an industry "Committee of 54" (formally known as the Emergency National Committee of the Petroleum Industry) foregathered in Chicago to draft a Petroleum Code. While the Committee may have been dominated by the API, it appears to have been representative of all phases and geographical sectors of the industry. [38] A preliminary draft of the proposed Code was submitted to the National Recovery Administration by mid-July, and a period of discussion within both the industry and the Government followed until the final form of the Code was approved by President Roosevelt on August 19.

Not all was sweetness and light in the drafting of the Code. As might be expected, the labor provisions required for approval were not happily received. A more fundamental disagreement within the industry arose over a provision directing the President, on a trial basis and for a limited period of time, to establish minimum wholesale gasoline prices within the various refinery districts [39] and to ensure minimum crude oil prices per barrel which were 18.5 times the average price of gasoline per gallon. [40] The independent refiners insisted that the 18.5:1 ratio was too high, the independents could not afford to pay such prices for crude in view of the contemplated base price for gasoline. The California independent refiners (represented by Will J. Reid and Ed Pauley) argued to the NRA Administrator that the average U.S. ratio should be 15:1. The majors and the independent crude producers, on the other hand, argued that expected crude prices were too low. One "Committee of Five", appointed at the last minute by the original Committee of 54, addressed a firm letter to General Johnson demanding "stronger provisions" for minimum crude prices, in view of the projected "enormous additions to labor costs" required by the Code and other anticipated increases in operating expenses. [41] Another "Committee of Five", representing 14 major integrated companies, feared that independent refiners would not abide by the Code allocations; they urged that provision be made for the "Federal Agency" to directly allocate and enforce quotas on any independent refiners who failed to conform under the regular quota procedure. [42]

In his letter forwarding the completed Petroleum Code to the White House, General Johnson (NRA Administrator) assured the President that it was fully endorsed by NRA's Labor Advisory, Consumer Advisory, and Industrial Advisory Boards. [43] What remains of the Code filed in the National Archives, however, suggests that opinion within Government was somewhat less unanimous than General Johnson implied. Thus, Joseph E. Pogue took exception to the price-fixing provisions and measures designed to raise crude prices: "One result may be the squeezing out of small refiners and small distributors." [44] W. F. Ogburn (of the Consumer Advisory Board) was even more critical of the entire code:

"1. The proration program of the code and the uniform marketing conditions make extremely probably (sic.) monopoly prices. The inelastic demand for petroleum increases the probability in this case. With restrictions of output these monopoly prices are likely to become high ...

2. The problem of administration of the code will in the long-run be found to be important. The large administrative body provided for in the code without appropriate government representation does not seem to be the best type of administrative body ..." [45]

Despite these and other objections, the code drafted by the industry, with little or no substantive revision, was signed by the President.

Two of the code's provisions may be quoted. The first of these was the long-sought antitrust exemption:

"Agreements between competitors within the industry for the purpose of accomplishing the objectives of this act, or any of them, or for the purpose of eliminating duplication of ... facilities are hereby expressly permitted ... (subject to the approval of the President)." [46]

The second dealt with the role of market forecasting and the control of crude oil production:

"Required production of crude oil to balance consumer demand shall be estimated at intervals by a Federal Agency designated by the President ...

The required production shall be equitably allocated among the several States by the Federal Agency." [47]

Among other provisions, the price-fixing clauses (with the 18.5:1 ratio) have been referred to. Imports were limited to the daily average for the last six months of 1932. Withdrawals of crude from storage stocks required approval of the Oil Administration. Wild-catting was not directly regulated, because of its importance to the "future maintenance of petroleum supply", but the shipments in interstate commerce of oil from new fields were developed in accordance with a plan approved by the President. And a series of "fair" marketing practices from the crude oil level down to retail service station operations was delineated.

Two other features of the Code should be mentioned. So far as crude allocations are concerned, the Federal Government prepared forecasts which were prorated among the States. [48] Interstate prorationing of State quotas among pools and fields was left up to the appropriate State agency—with, however, the provision that the President could designate such a State agency in any State (e.g., California) which failed to create one. Federal intervention was far more comprehensive as regards refinery operations. The country was divided into eight refinery districts, for each of which finished products quotas were established. Ultimately, within each district, a district (... missing part of the paragraph in the page break of the draft ...) refineries.

Ancillary to the Code, although not a part of it, was a section of the National Industrial Recovery Act designed to assist State prorationing agencies by prohibiting interstate shipments of "hot" oil (or products refined from hot oil). [49] The task of enforcing this section was entrusted to the Oil Administrator once the Code had been approved. The lack of success here was notable. Till suggests that the early approach of requiring a wealth of reports from shippers and refiners provided such a plethora of data that it could not be digested by the Petroleum Administrative Board, and, further, that the Oil Administrator received much less than full cooperation from the Department of Justice in prosecuting violations. [50] Ultimately, a Federal Tender Board appointed by the Oil Administrator for the East Texas field (the primary source of hot oil) in October 1934 gave some indication that it could cope with the problem. Within less than three months, however, the Supreme Court declared Section 9(c) unconstitutional, and the authority of the Tender Board evaporated. [51]

Much of the character of the Code in practice depended upon the administrative mechanism developed to enforce it. The Petroleum Code was unique among the NRA codes, in that nine days afters its adoption, the President transferred enforcement authority from the NRA Administrator to the Department of Interior. [52] The Secretary of Interior, Harold Ickes, was designated by the President as Oil Administrator.

Ickes was assisted by the Petroleum Administrative Board, headed by Nathan Margold, Interior Solicitor and a man whose record shows him to have been a good friend of the major petroleum companies. The other members of the board consisted of two attorneys and two economists. The Board's function was to implement the Code in terms of broad policy and to advise the Oil Administrator. The membership of the Board, as well as the Planning and Coordination Committee is shown in Table 1.

[No table showing the board membership was supplied in either the draft copy of this memorandum or in the published version. Roger M. and Diana Davids Olien's Oil and Ideology: The Cultural Creation of the American Petroleum Industry says (p. 197), "The Petroleum Administration Board was headed by Interior Solicitor Margold and included Yale jurists Norman L. Meyers and J. Howard Marshall, whose Yale Law Review articles indeed took them a long way; J. Elmer Thomas of Fort Worth; and John W. Frey of the Department of Commerce, who would later coauthor the official history of the wartime Petroleum Administration for War."]

As a practical matter, the real power in controlling all phases of the industry during the life of the Code rested with the Planning and Coordination Committee, the instrument of "self-government". The Committee originally consisted of twelve voting industry representatives, dominated by the majors, and three non-voting "observers" presumed to be on guard to protect the public interest. Significantly, two of the three "public interest" representatives were drawn from the petroleum industry itself. The third, Donald Richberg (NRA General Counsel) advocated a compulsory price-fixing program throughout every stage of the industry; when the Committee and the Board refused early in 1934 to adopt his plan, Richberg expressed his pique by personally boycotting any further meetings.

The Committee's power was particularly evident in the key areas of controlling refinery operations. The original Code, Article IV, conferred no power on any one to regulate actual refinery output; it simply stated the Planning and Coordinating Committee would appoint subcommittees within each of eight refinery districts which "shall call the attention of refiners within their respective districts to the existing and recommended ratios between gasoline inventories and sales within said districts." [53] In practice the district subcommittees immediately began establishing refinery operating quotas, with absolutely no legal basis to do so. The obvious illegality of this action led to an amendment of Article IV, virtually drafted in toto by a group of 24 majors. [54]

Control of refining operations was formally vested in the Planning and Coordination Committee by the amended Article IV. The Petroleum Administrative Board was charged with "recommending" a monthly national gasoline quota to the Committee, on the basis of Bureau of Mines forecasts. The Committee would decide on the actual quota and divide this among the refinery districts. Within each district, the district allocator (appointed by the Planning and Coordination Committee, i.e., by the major companies) would determine the quota of each refinery, with the district subcommittee filling the role of appeals agencies. As Watkins clearly shows, the Committee acted with complete autonomy in this area—it was not bound to, nor did it, follow the "recommendations" of the Board. Watkins, himself, notes with considerable sarcasm that this was all for the best: If refining were to be controlled in the interests of the country—

"... then it would seem to be better that market control be turned over to syndicated business entirely than to have it left in any degree subject to the dictates of an administrative officialdom so insensible to public interests." [55]

The detailed operations of the Code can best be seen in the case study of California. It is sufficient to say at this point that a relatively short period of Federal coercion, prior to the Schecter decision, was enough to fasten upon the industry the type of cooperation among industry, State, and Federal agencies which had been earlier advocated by the majors and the Oil Conservation Board. In essence this experience strengthened the willingness of States to practice prorationing not simply for physical conservation but to raise crude oil prices; it led to the early acceptance of the Interstate Oil Compact to coordinate State policies, it persuaded Federal officials, particularly in Interior, that they were truly the guardians of industry's welfare, and, certainly not least of all, it accustomed the vast majority of independents to passive acceptance or a role of staying in line with policies decreed for them by State and Federal agencies and their economic betters within the industry itself.

The operation of the Petroleum Code in California demonstrates the extremes to which cartelization could be carried under the National Industrial Recovery Act.

The dissolution of the Standard Oil Trust was followed shortly by a tremendous expansion of crude production in California; from 1918 through 1928, for example, the lead in domestic prduction seesawed between California and Oklahoma, with each leading Texas by a wide margin. [56] In the process of development, the industry structure came to be dominated by seven major integrated companies, with a small group of independent crude producers and refiners. [57] Two aspect of the refinery and distribution markets can be noted. First, the independent refiners usually sold "unbranded" gasoline which retailed at 2¢ - 3¢ per gallon below the majors—but from 1922 on there were frequent price wars, triggered by a widening of this differential. [58] Second, according to Watkins, very little of the independent refiners' output was marketed through exclusive outlets; nearly all of it was retailed by service stations operating on a "split-pump" basis—i.e., they carried major brands, but usually had a pump or two of "unbranded" independent gasoline. [59] Thus, the retail outlets for the independent refiners were vulnerable to pressure from the majors.

In 1928 the majors endeavored to counter the price wars with a cartel, the so-called "Long Pool" (after its manager, Frank R. Long). Cooperating independents agreed to maintain fixed price differentials below the majors for "third-grade" gasoline; [60] the majors, in turn, established a pool agency to buy up any "surplus" gasoline from the independents, to remove any economic pressures to cut prices. Presumably, non-cooperators were dealt with through a type of service station boycott which will be described more fully in connection with NRA regulation. Not surprisingly, the Department of Justice took a dim view of the Long Pool, proceeding to secure indictments against the participants. The case was settled in September 1930 by a consent decree which perpetually restrained the defendants from engaging in such "cooperation". [61]

The crude producers immediately turned to the subterfuge of conservation—establishing a "Central Committee of California Oil Producers" to engage in voluntary statewide prorationing. This Committee has continued operations to the present day, although its name has been changed to the more euphonious title, "Conservation Committee of California Oil Producers". In recognition of the potential antitrust weakness of this approach, the producers have three times—in 1931, 1939, and 1956—persuaded the State legislature to pass bills providing statutory authorization for the Committee to operate. Each time the bills were forced to popular referendum and soundly defeated. [62] Nevertheless, the Committee has continued to act as the prorationing authority in California—and, indeed, is hailed by most recent writers as an outstanding example of voluntary self-regulation, which has perhaps shown itself more capable to "maintaining stability" than most governmental agencies in other States. That this has been accomplished on a "voluntary" basis is, in fact, the direct inheritance of compulsory cartelization under NRA.

Within five days after his appointment as Oil Administrator, and with no public hearings, Secretary Ickes designated the Central Committee as "the State Agency" to enforce crude production quotas in California. [63] To cover refining and marketing, the majors next proposed an amazing program openly labelled "The Pacific Coast Cartel", to fix prices and sales quotas throughout the industry. This was described with clear approbation by Nathan Margold, Interior Department Solicitor, as: "... a cartel which assured all refiners of an adequate supply of crude, a fair share of the gasoline market based upon their historical and current record of sales, and provided adequate margins and stabilized prices for the retail trade." [64]

The cartel proposal was submitted to the Oil Administrator on January 30, 1934, and approved by him, on February 13, again with no public hearings, and modified only by a request that a representative of the Administrator be permitted to sit as an observer on meetings of the governing board.

The provisions of the cartel, according to Mr. Margold, led to certain objections by the Justice Department which were overcome by the negotiation of a new agreement. In fact, according to Watkins, Justice broke openly with Interior and promptly secured indictments against the cartel participants; the oil company lawyer—despite the Ickes' approval of the agreement—decided that discretion was the better part of valor and voluntarily dissolved the cartel.

It appears evident that in the efforts within the Executive family to heal this breach, Secretary Ickes was victorious. Justice, which could not look with favor upon the "Pacific Coast Cartel", was persuaded to accept the rose by another name, "The Pacific Coast Agency Agreement"—signed by the seven majors, one independent, and the Oil Administrator—and a collateral Refiners' Agreement on June 23, 1934.

The open price-fixing of the Cartel was accomplished less directly by the Agency Agreement. The Pacific Coast Petroleum Agency (i.e., the seven majors and one independent) was delegated the power to allocate the refinery quotas established for California by the Code's national body. Price-fixing was accomplished by means of two funds, contributed by the majors to the Agency and used in effect to guarantee sales quotas of the independents who signed the Refiners' Agreement. The Crude Oil Purchase Fund was used to buy surplus crude from signatory refiners who had more than needed to fill their refinery quotas (and in theory to provide crude to refiners who were short on crude). The Gasoline Purchase Fund was used to buy gasoline which the independents could not market at posted prices through their own outlets. The price at which this Fund stood ready to buy was established by a formula which guaranteed the signatory independent refiners the same "net price" to retailers (less agreed upon distributors' margins) as that charged to the retailers by the majors for third-grade gasoline.Under the Refiners' Agreement, the independents agreed to accept the quotas established by the Agency. Further, they agreed to police the established 3¢ per gallon margin between retail prices and the net price to retailers. Coupled with the net to refiners guaranteed by the Gasoline Purchase Fund, this completely eliminated price competition between the majors and the independent refiners: as Margold pointed out, "Under the agreement . . . independent companies are selling their gasoline at the same price as the major and affiliated companies' third-grade gasoline." [65] Finally, the Refiners' Agreement in Section XII(i) provided the most effective—and most obviously illegal—means of enforcement which could possibly be devised. All signatories agreed to boycott any service station which handled "hot gasoline" produced by any nonsigner or by any signatory in violation of the agreement or which cut retail prices below the 3¢ margin. Since, as stated earlier, nearly all of the independents' output was marketed by "split-pump" retailers, this meant that any service station which tried to sell "hot gasoline" in one pump would find itself cut off from suppliers for its other pumps.

Thus, under the NRA there was reestablished—with the aid, support, and blessing of the Department of Interior and without further open opposition by the Department of Justice—the very same course of action which had been perpetually enjoined by the Federal Court in the Long Pool Case! It must be admitted that Justice did insist on one further document. This was a third, supplementary agreement by which the participants in the other agreements indicated that they would voluntarily abide by the provisions of the Code and would not "engage in monopolistic practices". [66] Needless to say, since the entire structure created by the Agency Agreement rested completely on monopolistic practices, this supplementary document was nothing more than a face-saving device for the Justice Department.

The Oil Administrator officially cancelled the Pacific Coast Agency Agreement on June 3, 1935, a week after the Schecter decision. Nevertheless, one should not underestimate what was accomplished in a period of year [sic] under the Agreement. It is exceedingly doubtful that the Conservation Committee of California Oil Producers could have operated as successfully as it has over the past three decades—in the face of the existence of strong independents and outright rejection of any statutory authorization by the voters—without the experience in collusion gained during the NRA era.

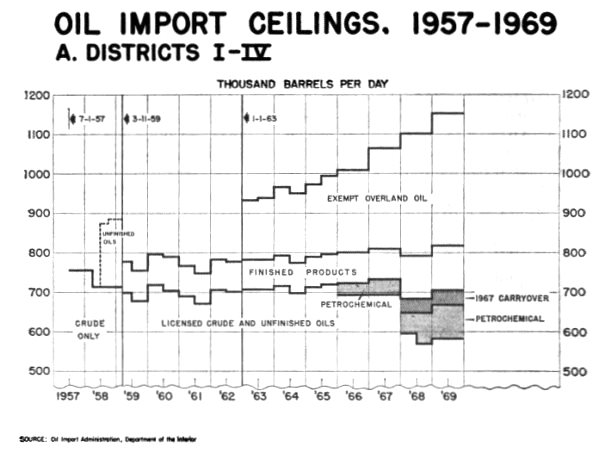

The attached chart (Chart 1) illustrates the changes in import ceilings for Districts I-IV from July 1, 1957, through the latter half of 1968. [Footnote 66a points to the chart below, found on page 316 in the document.] Three separate periods must be identified within the program. The first period, from July 1, 1957, through March 10, 1959, covers the Voluntary Program. The second, from March 11, 1959, through the second half of 1962, includes the initial phase of the Mandatory Program, in which imports were limited to 9% of demand. The third period, since January 1, 1963, shows the Mandatory Program as it operates at present. It should be noted that, as shown below, the ceilings of the three periods are far from comparable.

Throughout the memorandum information and data are taken from the Walter J. Levy Reference Handbook on the program and from public releases by the Oil Import Administration, Department of Interior. Finally, the memorandum is limited only to crude and unfinished oils, and finished products except residual.

The Voluntary Program represented the first true formal program to control imports. It succeeded an earlier, relatively informal attempt to persuade importers to cut back imports in 1956; this early effort could best be characterized as a series of "hold-the-line" exhortations from Dr. Arthur Fleming, OCDM Director, an approach which drifted into oblivion with the first Suez crisis.

The Voluntary Program instituted on July 1, 1957, was in a sense misnamed. Existing importers "voluntarily" agreed (under the threat of a mandatory program) to accept quotas established by Oil Import Administrator while newcomers were required to apply for permission to import at least six months before bringing in foreign crude. While sanctions other than the threat of mandatory controls were never very clear, [67] the program was effective in limiting imports of crude oil. It broke down because of (a) the loopholes for unfinished oils and finished products and (b) the lack of workable standards for the admission of newcomers.

Initially, the ceiling was established for crude oil only, theoretically at 12% of domestic production. From July 1, 1957 to March 31, 1958 the permissible level of imports into Districts I-IV was 755.7 thousand b/d; effective April 1, 1958, for the remainder of the program the ceiling was 713 thousand b/d (presumably reflecting a 9% decline in domestic production).

The apparent sharp rise in the ceiling shown on the chart reflects the inclusion of unfinished oils as of July 1, 1958. Importers had been quick to find this means of evading the original crude oil ceiling and by mid-1958 imports of unfinished oils had risen more than 100-fold from the 1,500-1,800 b/d level existing in the first half of 1957. As the chart shows, importers were instructed to hold unfinished oils to the May-June average of 160 thousand b/d for Districts I-IV, a figure which was subsequently raised to 172 thousand b/d. [68]

Imports of finished products (excluding residual) remained outside the ceiling under the Voluntary Program, although their rising level caused increasing concern within the Oil Import Administration. From a level of 67,000 b/d for the country as a whole in the first half of 1957 (prior to the Program), imports of finished products rose by 143% to 163 thousand b/d during the last half of 1958. [69]

It should also be noted in comparing ceilings in different periods, that there was no "overland exemption" under the Voluntary Program. Imports of crude, and later unfinished oils, from Canada were included both in the quota limitations and the overall ceiling.

Finally, in comparison to the later mandatory approach, the exchange system with its premium value for "tickets" did not then exist. All imports had to be for the direct account of the importer. [70] Thus, only those refiners who could actually utilize foreign crude (in terms of refinery design and geographical location) were in a position to apply for import quotas. At the same time the economic advantages of foreign crude to those refiners in a position to run it were not nullified by the premium payments for tickets which developed later under the Mandatory Program.

The breakdown of the Voluntary Program led to the imposition of the Mandatory Program effective March 11, 1959. The changes embodied in the new program had a significant effect on the import ceiling.

The magnitude of this effect can best be seen by examining the level of imports under the Voluntary Program in the latter half of 1958. The basic ceiling for Districts I-IV, at 12% of production, came to 713,000 b/d of unfinished oils and an amount of unregulated finished products sufficient to bring the permissible level of imports well above one million b/d. [71]

Under the Mandatory Program, from March 1959 through 1962, the overall ceiling for crude and unfinished oils and finished products was set at 9% of forecast demand (equivalent to about 10% of production). Thus, the overall ceiling for the second half of 1959 amounted to 754,600 b/d, a reduction of at least 25% from the permissible level under the second half of 1958.

Within the overall ceiling, in what was perhaps the most arbitrary aspect of the new program, a ceiling was established on both the amount and the importers of finished products, principally gasoline. The amount was fixed at 76,634 b/d, the 1957 average, and licenses to import finished products were limited to those importers of record during 1957. The largest share of this (30,554 b/d) was reserved for the Department of Defense. More than half of the 46,080 b/d available to private importers went to Jersey Standard and Shell. These two companies, followed by Standard of California, Pittston (through its acquisition of Metropolitan Fuels), Hess, and Gulf accounted for 93% of the amount allocated to 15 private firms. It is true that Proclamation 3328 (December 10, 1959) provided that allocations would be made to newcomers on the basis of "exceptional hardship". But for eight years the Oil Import Appeals Board failed to find any such hardship cases. In 1967 all finished products quotas including DoD's were reduced proportionately to establish a 5,000 b/d set-aside for hardship allocations.

The fixed quota for finished products was subtracted from the overall ceiling (9% of demand) to yield the ceiling for imports of crude and unfinished oils. [72] The latter two categories were combined into a single category, with the provision that no company could import more than 10% of its quota in the form of unfinished oils. While the Secretary was given the power to vary this percentage, it, too, was held fixed until 1967, when it was raised to 15%.

The impact of the Mandatory Program is most clearly indicated here. In the seven full allocation periods from the last half of 1959 through 1962, the permissible level of crude and unfinished oil imports averaged 695,000 b/d, a reduction of nearly 200,000 b/d from the 885,000 b/d allowed under the separate crude and unfinished ceilings during the latter part of the Voluntary Program.

To some extent the reduction in ceilings was eased by Proclamation 3290 (April 30, 1959) which established, as of July 1, 1959, the "overland exemption". These imports were exempted from both quota provisions and from the ceiling itself; i.e., the ceiling now related only to imports brought in over water. While there was little opposition to this exemption at the time, it developed rapidly as imports of exempt oil rose.

With the import ceiling established as a percentage of domestic demand and with overland imports made exempt from the ceiling, any increase in overland imports would obviously displace an equivalent volume of domestic production, rather than reducing foreign waterborne imports. This is precisely what happened. In the last half of 1959, Canadian imports into Districts I-IV averaged 56,000 b/d, while the Brownsville Loophole had not yet been invented. By the last half of 1962, exempt overland imports had risen by nearly 100,000 b/d (displacing this additional quantity of domestic production), with Canadian imports of crude and products at 121,000 b/d and with 30,000 b/d of Mexican "overland" oil coming in through Brownsville. This was the rock upon which the first phase of the Mandatory Program foundered.

At the same time, the ceiling amount of crude and unfinished oil was allocated among all companies having refining capacity, whether or not they could actually utilize foreign oil. This immediately led to the growth and exchanges between inland refiners (who received tickets they could not use) aud coastal refiners (who needed tickets which they did not have). A trade developed between the two groups in the exchange of tickets under which their value soon became stabilized at $1.25. The practice eliminated most of the economic advantages of East Coast refiners in running foreign oil. [73]

The second and current phase of the Mandatory Program was inaugurated on January 1, 1963 (pursuant to Proclamation 3509, November 30, 1962). A principal change was a return rather than demand (as in the Voluntary Program) to a ceiling based upon domestic production. The new ceiling in Districts I-IV for imports of crude and unfinished oils and products (except residual) was established at 12.2% of forecast domestic production of crude oil and natural gas liquids.

Another major change was in the treatment of overland imports from Canada and Mexico. These imports remained free of licensing and company allocation requirements, but they were brought within the overall ceiling; i.e., estimated overland imports for an allocation period are now "taken off the top" of the ceiling in order to arrive at the figure for permissible imports from other foreign sources. Thus, in contrast to the Voluntary Program, overland imports are now treated more generously than other foreign imports. The "estimated" amounts (30,000 b/d for Mexico and a steadily increasing volume, from 120,000 b/d in 1963 to 280,000 b/d in 1968, for Canada) are arrived at through intergovernmental negotiations. At the same time, in contrast to the original form of the Mandatory Program, "exempt" overland imports are within the ceiling, so that any increase in overland imports displaces other foreign oil rather than domestic production.

In the case of finished products both the amount (76,634 b/d) and the historical company allocations established in 1959 remained inviolate through 1966. For 1967 the ceiling was retained, but in response to growing complaints about the shortage of product to Northeastern fuel oil dealers and terminal operators, OIA withheld 5,000 b/d to create a set-aside from which hardship quotas could be granted—some seven years after the proclamation authorizing such hardship quotas had been promulgated.

The first real breach, however, did not come until 1968. The set-aside was increased to 7,000 b/d, but this was only the beginning. Quotas of the historic importers were then reduced by another 15,000 b/d to "make room for" Hess to bring this amount in from the Virgin Islands. Next the ceiling was increased by 30,800 b/d of gasoline from Puerto Rico—20,800 b/d from Phillips and 10,000 b/d from Commonwealth.

All three of the latter transactions have unusual features. The Hess operation starts with a Virgin Island refinery, able to run inexpensive foreign oil outside the quota, i.e., with no offsetting ticket premiums. Next, existing East Coast importers of finished products have had their allocations cut by 15,000 b/d for the benefit of Hess, on Hess' promise that a large part of this will be heating oil for the Northeast, where Hess itself is a major fuel oil dealer. In other words, Hess is now in a position to increase its own share of the Northeastern fuel oil market on the basis of far cheaper supplies than those available to any of its independent competitors.

Phillips was granted a 50,000 b/d crude quota for its new Puerto Rican petrochemical facility. Starting with inexpensive foreign crude, it can ship petrochemicals (including such feedstocks for further processing as benezene, xylene, and toluene) into the mainland U.S. duty-free at far lower costs than those faced by the company's competitors in chemical markets. But in producing petrochemical feedstocks from crude oil an "inevitable" by-product is gasoline; for Phillips, Interior accepts up to 48% of total output in the form of gasoline as reasonable. While Phillips might have been told to dispose of this "by-product" wherever it could elsewhere in the world. Interior decided that the company could market 20,800 b/d in 1968 (ultimately, 24,500 b/d) on the East Coast.

Finally, the arrangement for Commonwealth Oil Refining Co.. like that of Phillips', arises from Puerto Rican chemical production. When the company's petrochemical operation went onstrearn in 1966, it found itself with a surplus of gasoline which it could not market on the East Coast. [74] Thereupon, with the knowledge and approval of Interior, Commonwealth entered into a contract to supply 10,000 b/d to an independent West Coast distributor, Ashland Oil. Ashland pursued a vigorous competitive policy, holding down prices in its own stations and, as a wholesaler, supplying other competitive independent operators. Interior was then deluged with protests from West Coast majors and independents that this "unfair" competition was made possible by cheap gasoline from Puerto Rican gasoline [sic]. [75] In December 1967, with no prior announcement or public hearings, Interior amended the control program to eliminate these shipments, depriving Ashland of its contractual supply from Commonwealth. At the same time Interior granted Commonwealth the right to ship an additional 10,000 b/d to the East Coast, thereby saving Commonwealth approximately $1 million a year in transportation charges—within the overall ceiling, but over the prior finished products ceiling.

Thus, the ceiling for finished products (excluding residual) is now 107,436 b/d. Of this 21,783 b/d remains in the DoD allocation, which has not been utilized for several years, presumably to help the nation's balance of payments problem. The effective ceiling for civilian importers, therefore, is 85,653 b/d. Nearly 60% of this quota goes to what are now the three leading importers—Phillips with 20,800 b/d, Hess with 18,136 b/d (15,000 from the Virgin Islands and the remainder from its historic import position), and Commonwealth with 10,000 b/d. Each of the first two now has more than the combined quotas of Jersey Standard and Shell, the former leaders.

With exempt overland and finished product imports coming "off the top", the amount of crude and unfinished oil permitted—i.e., the amount of foreign oil available to East Coast refiners—averaged 710,000 b/d from 1963-65—about the same order of magnitude as that allowed in the first phase of the Mandatory Program. The increase in the overall ceiling generated by rising domestic production accrued almost entirely to the Northern Tier refiners, running exempt Canadian oil. It should also be noted that Canadian imports, since they are not licensed, generally exceed Interior's "forecast". During the first eight months of 1968, for example, actual imports averaged 300,000 b/d as compared to the 280,000 b/d forecast; for July and August alone, the forecast was exceeded by 65,000 b/d.

The initiation of petrochemical quotas for crude and unfinished oils in 1966 provided another check upon any growth in foreign supplied for East Coast refiners. In 1966 the petrochemical allocations totalled 30,000 b/d leaving for petroleum refineries 693 thousand b/d out of a total foreign crude allotment (above exempt imports) of 722 thousand b/d. In 1967 both the non-exempt crude ceiling and petrochemical quotas were raised by about 10,000 b/d, leaving the refinery supply virtually unchanged.

For 1968 the overall 12.2% ceiling for crude and products was raised by some 46,000 b/d through a forecast increase in domestic production. [76] Despite this, however, the amount of foreign crude allocations to refineries outside the Northern Tier was sharply cut, as the result of a 121,000 b/d rise in the volume of "off-the-top" items. Estimated Canadian imports for the Northern Tier companies went up by 55,000 b/d, while as stated earlier, the finished products ceiling was raised by 30,800 b/d for the benefit of Phillips and Commonwealth. The remaining off-the-top item, 35,700 b/d, represents a carryover of unused 1967 tickets, charged against the 1968 ceiling (an equal amount could be brought in above the 12.2% ceiling). [77] From discussions in the trade press during the fall of 1967, it appears that Interior's handling of these tickets in the face of the post-Suez crisis was motivated chiefly by a desire to preserve the $1.25 ticket value; had uncommitted 1967 tickets been thrown on the open market, the entire exchange premium system would have been in chaos. [78] The net effect of the increase in the overall ceiling with a much greater rise in off-the-top deductions was a fall in the amount of crude available for new 1968 allocations (to refiners and chemical companies) to 646,160 b/d, the lowest level in the program's history.

It is against this background that domestic refiners have protested against an increase in petrochemical quotas to 52,000 b/d for the first half of the year and to 79,000 b/d for the second half. On their part the chemical companies make two observations.

First, the increase from 1967's 40,000 b/d to 52,000 b/d in the first half of 1968 may have been more than double the rise intended by Interior. The final ceiling included 7,213 b/d for Standard of Indiana, which under the existing regulations successfully claimed a petrochemical quota for its production of a common gasoline additive. [79] A rewriting of definitions eliminated this Loophole for the second half of the year.

Second, the further rise to 79,000 b/d for the second half of 1968 was not, in fact, a change in petrochemical quotas, but rather a "paper" transfer to petrochemical quotas of refinery crude quotas formerly held by chemical companies—although individual firms might well dispute the statement that there was no essential change. Several chemical companies, such as Allied Chemical, Celenese, Dow and Monsanto had held crude quotas based on refinery operations even before there were petrochemical quotas. In addition, nothing in the OIA regulations prevented oil companies such as Jersey Standard, Shell, and many others from using refinery crude allocations, based in part on the production of petrochemical feedstocks, for their own extensive chemical operations. The original petrochemical crude regulations were so drawn as to permit most of these companies a "double dip"—i.e., a refinery crude quota plus a petrochemical quota for downstream inputs of petrochemical feedstocks produced from oil imported under their own refinery quotas.

For the second half of 1968, the program was altered to eliminate the "double dip," while at the same time company allocations were raised from 8.35% to 11.3% of feedstock inputs. Between the changes in definitions and the increased ratio, some chemical companies which had not held refinery quotas secured increased petrochemical quotas. By and large, chemical companies which had enjoyed the double dip incurred substantial cutbacks in their combined quotas. Between the first and second halves of 1968 Dow, for example, lost more than 300 b/d, Eastman Kodak over 800 b/d, Union Carbide over 1,000 b/d, and Monsanto more than 1,300 b/d. Surprisingly, several major petroleum companies with chemical production managed to increase their combined refinery and petrochemical crude allocations; Jersey Standard, for example, picked up more than 1,600 b/d from the changes. The effects of the changes on individual companies holding petrochemical crude allocations are tabulated in Appendix II. In total, the increase of 27,000 b/d in petrochemical allocations from the first half to the second half of 1968 was almost exactly balanced by a reduction of more than 26,000 b/d in refinery crude allocations of companies eligible for petrochemical quotas.

In evaluating the impact of petrochemical allocations on the decline in the amount of foreign crude available for non-chemical refiners from over 700 thousand b/d in 1963 to roughly 560 [thousand] b/d in the last half of 1968, it cannot be denied that 79 thousand b/d [of petrochemical allocation] is a significant amount. But this should not be permitted to disguise the fact that the impact has been as great as it has because of other Interior decisions permitting the entire increase in the overall ceiling to be diverted to the benefit of importers of Canadian oil and to preferential treatment for Phillips and Commonwealth.

Perhaps the most convenient way to summarize the present status of the oil import program in Districts I-IV is to present it in the form of the table below, for the second half of 1968:

| TABLE 1.—Oil import control programs, districts I to IV 1968, second half | |

|---|---|

| [1,000 barrels per day] | |

| 1968 production forecast, districts I to IV | 9,028.0

|

| Overall ceiling, 12.2 percent of production | 1,101.4

|

| Less exempt overland oil: | |

| Canada | 280.0

|

| Mexico | 30.0

|

| Total | ( 310.0)

|

| Less finished products: | |

| Historic importers | 54.6

|

| OIAB set-aside | 7.0

|

| Hess, Virgin Islands | 15.0

|

| Phillips, P.R. | 20.8

|

| Commonwealth, P.R. | 10.0

|

| Total | ( 107.4)

|

| Balance, non-exempt crude and unfinished | 684.0

|

| Less 1967 carryover under 1968 ceiling (Allocated) | ( 35.7)

|

| Less petrochemical | 72.2

|

| Newcomer set-aside | 6.8

|

| Total | ( 79.0)

|

| Balance, refinery crude and unfinished | 569.3

|

| Less set-asides: | |

| OIAB | 2.0

|

| Newcomers | 5.0

|

| Sequoia Ref.1 | 2.1

|

| Total | ( 9.1)

|

| Balance, allocated as of July 9, 1968 | 560.2

|

| 1 To correct "administrative OIA error in 1967". | |

| Source: Department of Interior press releases, July 9 and July 24, 1968. | |

District V consists of the states west of the Rockies—California, Oregon, Washington, Arizona, Alaska, and Hawaii. From the time of the Voluntary Program it has been treated separately from Districts I-IV. In contrast to Districts II-IV, the West Coast has long been an oil deficit area (although this may change with the development of Alaskan fields). At the same time the Rockies constitute a barrier which has limited the growth of a pipeline network such as that which links the oil-deficient East Coast with the mid-continent. [80] While the approach in District V has differed from that in Districts I-IV, the program on the West Coast has shown a consistency which makes it far easier to describe and to understand.

Basically, the import ceiling is determined by the gap which exists between OIA estimates of demand and supply in District V. The terms themselves, of course, must be clarified. District V "demands" includes the requirements for (i) consumption within the district, (ii) shipments to other districts, and (iii) exports. "Supply" encompasses (i) production within District V, (ii) receipts from other districts, and (iii) overland Canadian imports. The difference is the amount of oil from foreign sources, other than Canada, available for company allocations.

The concept of the supply-demand gap may be conveniently illustrated by the actual 1967 data from the Bureau of Mines' Mineral Industry Surveys, arranged in Table 2 below:

| District V, supply and demand for crude petroleum and petroleum products 1967 | |

|---|---|

| [Thousands of barrels daily] | |

| Demand: | |

| Product demand in district V | 1,661

|

| Shipments to other districts | 28

|

| Exports | 90

|

| Total demand, district V | 1,779

|

| Supply: | |

| Production, crude and NGL | 1,139

|

| Receipts from other districts (crude and products) | 270

|

| Overland Canadian crude | 185

|

| Total supply, district V | 1,594

|

| Supply deficit | 185

|

| Source: "Crude Petroleum and Petroleum Products, December 1967," Mineral Industry Surveys, Bureau of Mines, March 22, 1968. | |

These figures indicate that had Interior been able to forecast perfectly, the 1967 ceiling for imports, other than Canadian, would have been 185,000 b/d in District V. The actual 1967 forecast and the volume of import tickets issued were for a deficit of nearly 226,000 b/d. The source of the difference is easily pinpointed: the importers of exempt Canadian oil (Texaco, Shell and Mobil) brought in 41,000 b/d more than the amount (144,000 b/d) originally estimated by Interior. As a result, supply in 1967 exceeded demand and stocks rose sharply at a rate of 38,000 b/d or nearly 14 million barrels over the course of the year, leading to a further cutback in the ceiling for 1968.

The movements of the District V ceiling from 1957 to date are shown on Chart II (or I-B) [below], with supporting data in Appendix I. It may be noted that rigorously (in the terms of the Proclamation) overland Canadian imports are added to domestic supply and the total is subtracted from demand to arrive at the technical import ceiling. To provide a better comparison with the chart for Districts I-IV, the ceiling shown on the chart for District V includes overland imports; this procedure is followed in Levy's reports and, indeed, in recent press releases of OIA itself.

The first voluntary ceiling was set at 220,100 b/d; from July 1, 1958, for the remainder of the program, it was 221,100 b/d. Nor did the unfinished oil loophole create any serious problem. While the West Coast was included in the national ceiling, the amount involved in Distrivt V was only 7,300 b/d (4,700 b/d for Union and 2,600 for U.S. Oil & Refining). As in the rest of the country, no special treatment was provided for Canada.

The supply-deficit concept was carried through into the Mandatory Program, the principal changes being that imports of unfinished oils (which had been minor) were brought under the ceiling, and imports of finished products (also minor) were limited to the average 1957 level. An interesting aspect is that the supply-deficit approach avoided the exempt Canadian oil problem which existed in Districts I-IV from July 1959 through 1962. It will be recalled that east of the Rockies during this perod when Canadian oil was both exempt from quotas and outside the ceiling, as then defined, increases in Canadian imports displaced domestic production; in contrast, within District V the definition of Canadian oil as part of supply meant from the beginning that increased Canadian imports would displace other foreign imports.

Another item is worth mentioning only because it is recorded in Appendix I, but does not appear on the chart. In December 1960, the Secretary ruled that estimated shipments from District V to other districts in excess of their 1958 level should be excluded from demand in calculating the ceiling. Pursuant to this, the demand estimate and hence the ceiling for the first half of 1961 were reduced by 11,500 b/d. On June 30, 1961, the Appeals Board (in an appeal brought by Texaco) ruled that this action could not be taken with a new Presidential Proclamation; the cut was automatically restored, outside the ceiling, in the second half of the year.

From the beginning of the Mandatory Program through the first half of 1965, the overall ceiling (including Canadian imports) rose more or less steadily, more than doubling from 211,000 b/d at the outset of the Program to 474,000 b/d for the first half of 1965. As has been true in Districts I-IV, Canada was the principal beneficiary; the Canadian import forecast rose from 22,005 b/d for the last half of 1959 (actual imports from March 11-April 23, 1959) to 155,000 b/d for the last half of 1965 and for 1966. It should be noted that in District V exempt Canadian imports benefit only three companies—Texaco, Mobil and Shell—which have refineries north of Seattle.

Finished product imports have been held constant at 10,679 b/d since the second half of 1961; even this figure is an increase of only 60 b/d over the amount instituted originally in 1959. In District V, more than one-third of the finished products quota is accounted for by a Department of Defense residual fuel allocation, leaving a finished products quota comparable to that in Districts I-IV of only 6,813 b/d (of which 500 b/d has been set aside for OIAB in 1967 and 1968).

Despite the increase in exempt Canadian oil, the ceiling grew rapidly enough to the first half of 1965 to permit a sizeable growth in permissible imports of other crude and unfinished foreign oil, from an initial level of 200,000 b/d (March-June 1959) to 322,000 b/d (January-June 1965). Since that time rising California production and the development of Alaska's Cook Inlet has steadily displaced foreign oil. The amount available for crude and unfinished oil allocations in the second half of 1968 was 155,000 b/d. 20% below the level at the start of the Mandatory Program and less than half the January-June 1965 peak.

Other adjustments to the crude and unfinished oil ceiling in District V in recent years have been similar to, but much less in magnitude, than those in Districts I-IV. Thus, there have been OIAS set-asides of 1,000 b/d in 1967 and 500 b/d in 1968 for hardship cases; in addition, a newcomer set-aside of 2,000 b/d was established in the latter half of 1968.